STOPTIME: Live in the Moment.

Ranked in the top 5% of podcasts globally and winner of the 2022 Communicator Award for Podcasting, STOPTIME:Live in the Moment combines mindfulness, well being and the performing arts and features thought provoking and motivational conversations with high performing creative artists around practicing the art of living in the moment and embracing who we are, and where we are at. Long form interviews are interspersed with brief solo episodes that prompt and invite us to think more deeply. Hosted by Certified Professional Coach Lisa Hopkins, featured guests are from Broadway, Hollywood and beyond. Although her guests are extraordinary innovators and creative artists, the podcast is not about showbiz and feels more like listening to an intimate coaching conversation as Lisa dives deep with her talented guests about the deeper meaning behind why they do what they do and what they’ve learned along the way. Lisa is a Certified Professional Coach, Energy Leadership Master Practitioner and CORE Performance Dynamics Specialist at Wide Open Stages. She specializes in working with high-performing creative artists who want to play full out. She is a passionate creative professional with over 20 years working in the performing arts industry as a director, choreographer, producer, writer and dance educator. STOPTIME Theme by Philip David Stern🎶

🌟✨📚 **Buy 'The Places Where There Are Spaces: Cultivating A Life of Creative Possibilities'** 📚✨🌟

Dive into a world where spontaneity leads to creativity and discover personal essays that inspire with journal space to reflect. Click the link below to grab your copy today and embark on a journey of self-discovery and unexpected joys! 🌈👇

🔗 [Purchase Your Copy Here](https://a.co/d/d3FLZRo)

🌟 **Interested in finding out more about working with Lisa Hopkins? Want to share your feedback or be considered as a guest on the show?**

🔗 Visit [Wide Open Stages](https://www.wideopenstages.com)

📸 **Follow Lisa on Instagram:** [@wideopenstages](https://www.instagram.com/wideopenstages/)

💖 **SUPPORT THE SHOW:** [Buy Me a Coffee](https://www.buymeacoffee.com/STOPTIME)

🎵 **STOPTIME Theme Music by Philip David Stern**

🔗 [Listen on Spotify](https://open.spotify.com/artist/57A87Um5vok0uEtM8vWpKM?si=JOx7r1iVSbqAHezG4PjiPg)

STOPTIME: Live in the Moment.

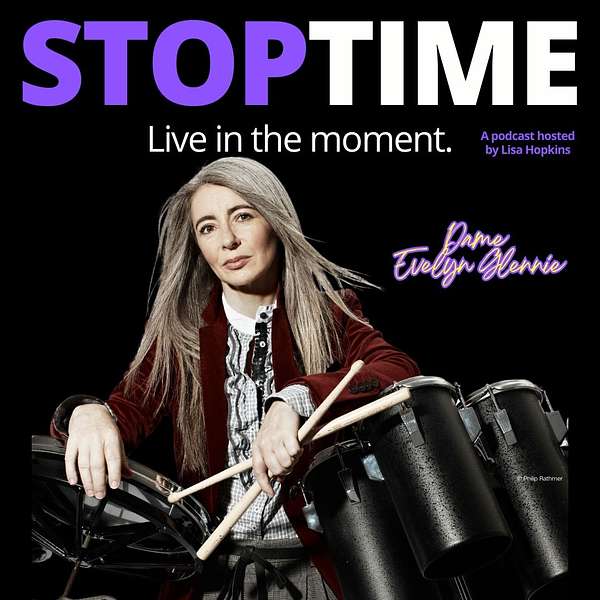

Dame Evelyn Glennie: The Art of Listening

Let us know what you enjoy about the show!

In the world of sound and silence, few have navigated the intricacies of deep listening as profoundly as Dame Evelyn Glennie. Our latest podcast episode unveils the remarkable journey of this virtuoso percussionist, whose life story is a symphony of resilience, innovation, and unwavering curiosity. From the prestigious halls of Robert Gordon University to the imaginative minds of children, Glennie's experiences transcend the boundaries of music, inviting us to consider the full spectrum of listening.

Evelyn Glennie's tale begins in the pastoral landscapes of Scotland, where a young musician, undeterred by her hearing impairment, confronted the classical music industry's rigid perceptions. Her audacity to challenge a rejection from the Royal Academy of Music not only paved her path to success but also revolutionized the admission process for artists with disabilities. The episode delves into the ethos of her secondary school that nurtured each child's unique potential, revealing how early educational environments can be instrumental in shaping one's future.

As the narrative unfolds, Glennie's philosophy of living in the moment becomes the central theme. She articulates the importance of being present, whether it's during a solo performance or a fleeting interaction. The discussion probes into the essence of practice, transforming the mundane into moments of potential and creativity. By redefining dynamics, not as mere musical notations but as emotional experiences, Glennie invites us to listen beyond the surface.

The impact of solo percussion on the musical world is another highlight, where Glennie shares her career's pivotal moments, including the normalization of solo percussion as a viable career path. The establishment of a substantial repertoire for solo percussionists is discussed, marking a triumph in the world of music that echoes Glennie's enduring influence.

As the episode nears its conclusion, we explore the importance of preserving musical heritage through the Evelyn Glennie Foundation and Collection. This repository of musical stories serves as a beacon for future generations, emphasizing the need to maintain a connection with our cultural past. The episode also touches on Glennie's personal interests, from working with animals to creating jewelry

If you are enjoying the show please subscribe, share and review! Word of mouth is incredibly impactful and your support is much appreciated!

🌟✨📚 **Buy 'The Places Where There Are Spaces: Cultivating A Life of Creative Possibilities'** 📚✨🌟

Dive into a world where spontaneity leads to creativity and discover personal essays that inspire with journal space to reflect. Click the link below to grab your copy today and embark on a journey of self-discovery and unexpected joys! 🌈👇

🔗 Purchase Your Copy Here: https://a.co/d/2UlsmYC

🌟 **Interested in finding out more about working with Lisa Hopkins? Want to share your feedback or be considered as a guest on the show?**

🔗 Visit Wide Open Stages https://www.wideopenstages.com

📸 **Follow Lisa on Instagram:** @wideopenstages https://www.instagram.com/wideopenstages/

💖 **SUPPORT THE SHOW:** [Buy Me a Coffee] https://www.buymeacoffee.com/STOPTIME

🎵 **STOPTIME Theme Music by Philip David Stern**

🔗 [Listen on Spotify]

https://open.spotify.com/artist/57A87Um5vok0uEtM8vWpKM?si=JOx7r1iVSbqAHezG4PjiPg

This is the Stop Time Podcast. I'm your host, lisa Hopkins, and I'm here to engage you in thought-provoking, motivational conversations around practicing the art of living in the moment. I'm a certified life coach and I'm excited to dig deep and offer insights into embracing who we are and where we are at. So my next guest is the first person in history to create and sustain a full-time career as a solo percussionist, performing worldwide with the greatest orchestras and artists of our times. She is a double Grammy Award winner and a BAFTA nominee and has commissioned over 200 new works for solo percussion and is recorded over 40 CDs.

Speaker 1:She is the first percussionist to be awarded the Dame Commander of the British Empire and the youngest person ever to be elected to the PAS Hall of Fame as a profoundly deaf musician and role model. Her significance transcends the discipline of music. Her unique skills as expert listener and sound creator have driven progress and innovation in a wide array of contacts on a global scale. She is on a lifelong mission to teach the world to listen and in 2023, she founded the Evelyn Glene Foundation, which aims to improve communication and social cohesion by encouraging everyone to discover new ways of listening in order to inspire, create and engage and empower. I am so, so, very thrilled and honored to have her here with me today on Stop Time and, without further ado, would like to introduce you to my next guest, dame Evelyn Glene. Welcome.

Speaker 2:Thank you very much. Thank you for the opportunity.

Speaker 1:It is brilliant to have you here. Where are you calling in from?

Speaker 2:Well, I'm at my office in Cambridge in England.

Speaker 1:Okay, and is that home base for you?

Speaker 2:This is where everything happens, this is the home base and, yes, I've been here for a number of years, which is a really convenient area to work from and to travel from. So, yes, everything happens here.

Speaker 1:You're in the room where it happens, so to speak.

Speaker 2:Absolutely In the engine.

Speaker 1:Absolutely. That's wonderful. And are you? You're in the countryside, I'm guessing yes.

Speaker 2:Well, I live in the countryside and the office here is based in a small town nearby to where I live, and so, yes, and the team is just busy around the building, so it's lovely.

Speaker 1:Wonderful. What are you getting ready for right now If you've got something coming up?

Speaker 2:Well, there's always something coming up where obviously we need deep in foundation activities. It is a very young foundation, and so we're still putting the nuts and bolts together. And then in the next day or two I head up to Scotland because I'm Chancellor of Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen, and so it's their winter graduations and that's always a very exciting time for a great number of students, and I certainly know what that feels like, having gone through the process myself. So and it's just again an opportunity to kind of cement the power and partnerships through listening and to engage with that. And then leading up to Christmas and just sort of little bits and pieces. And actually we have a wonderful online session with a school in California, a little primary school in California, and so I'll be taking out some of the weird and wonderful instruments for them.

Speaker 1:Wonderful. In my research I watched you years ago. I think it was on Sesame Street. I so enjoyed that.

Speaker 2:Yeah, absolutely, that was a fun day.

Speaker 1:It's. I mean that's where it all begins, right with the children, where they're just so open.

Speaker 2:It absolutely does. And I mean they're the greatest improvisers. We have, the most curious people, you know, most upfront, most kind of elastic minded folks that we have, and it's just so wonderful. You know, when you observe and when you interact with kids you never know quite what's coming, and that keeps us on our toes, I think, as adults. But it is keeping that kind of curiosity and elasticity in the thinking, in the imagination, that I'm really keen to acknowledge and allow the kids to forever explore and to keep that as a major trait throughout their life and no matter what landscape or profession you find yourself in.

Speaker 2:There is a form of creativity there and you know I often think about my own journey and all the years I've been doing what I've been doing, and why is it that I wake up in the morning still wanting to do what I do? And you know there are lots of days whereby I don't want to practice or I don't want to do this or I don't want to do that. But what overrides that is the sense of curiosity, is the sense of kind of peeling the next layer and seeing what might be there, because you realize, you know, sort of a long ago you've realized that well, actually things don't always go your way, or you might try really hard at something and it still doesn't quite reach the mark, but that's okay, and I think you're able to put things in perspective the older you become, and so you can let go a lot of that thought as well.

Speaker 1:Yeah, no, amazing, and yeah, I hear you. And with children, they don't have any editing, which is a wonderful thing, and it's a sad thing that we as adults sort of teach them how to edit and we use the word listen, as you know, be quiet, basically.

Speaker 2:No, absolutely You're right there. And I think a lot of the vocabulary we use, certainly when we're exposing kids to learning instruments and so on from that very young age, is, you know, vocabulary can affect so much of what they think, what they do. And you know, even if you're sort of thinking about musical vocabularies, you know something as basic as dynamics. You know F equals loud, p equals soft and so on. Well, what does that mean actually? What is loud in this room that I'm in today? You know what is loud in a library, what is loud out in a sporting arena. You know what is loud in a bus, what is loud in an aeroplane.

Speaker 2:And you know, I think that when we can sort of build around those words, the story, you know kind of a misty soft or a friendly loud or a spongy loud or an aggressive loud or a fragile soft or something, then you've got a bit of emotion there. But if you're asking a child just to play softer, you know they usually come at it from a physical point of view, ie they've got to do something physically less. Well, something can be made softer by thinking about it, and so the whole body is then engaged in the story of that dynamic. So you know, that's just a little example.

Speaker 1:No, 100%, and you're completely speaking my language, which is why I really wanted to connect, because, as a life coach, you know we talk about our thoughts, which are just energy right, they're energy. And then we think, talk about our context, right, which is what you're talking about. What words we use are so important for what stories we play in our heads, you know so, you're absolutely right. I mean, I completely identify with that. You know, what soft is to Evelyn today is very different. What soft to Evelyn even in the same room? Right, because you have an internal context as well as the external things which you're considering for whatever it is you're creating.

Speaker 2:Absolutely, and what's interesting, I think, is that now, of course, we're connecting with audiences and people digitally, whereby we're trying to get our craft over it through digital means, and of course, dynamics then have a whole different dimension because they're no longer physical, and I think that's really really interesting and it changes.

Speaker 2:You know what we do, and certainly the pandemic, you know where suddenly we're thrust in our living rooms and kitchens and expected to perform, you know, was something that certainly, in my mind, didn't work for me personally, and so I didn't engage with that, and I think that, you know, for some people it works really well, for others, like myself, it certainly didn't, and it just something, it was something that, you know, didn't give me any emotional pleasure, I had no connection with it whatsoever. So I think that it goes back to listening to what is it within yourself that makes you tick, that makes you function well, that makes you provide a level of an experience that is good for you, because if it feels good for you, normally that will be seen then and felt by the audience.

Speaker 1:Yep, absolutely. We're talking about how we can tap into what makes us, what needs to be in place for us to be the most effective we can be, so that we can then connect right With our values, which, in your case, obviously, is a large one, is expressing yourself through the music, but not just to play music right, it's way beyond that, clearly, which is brilliant. I love that. Hey, would you be willing to take us back a little bit to that moment when you were, I think, just 16 years old, where, despite all odds, you were stepping into an audition right for the Royal Academy of Music in London? Can you take us back?

Speaker 1:I'm really curious about the moment and anyone that there's so much research on Evelyn. So, my listeners, please, you know that you can go and find out on our website and all sorts of things and you'll learn through our conversation what happened to her. But I do you know anyone auditioning period for any kind of an organization like the Royal Academy of Music. You know, and my listeners can identify with this, that's a big deal, let alone being the age you were and you know and etc. So talk to me about that moment, if you can remember it, if you can sort of embody how you felt going in. What was your mission? Where were you? What was going on for you then? Can you tap into that?

Speaker 2:Well, I basically obviously was still at school in Scotland and I was waiting for exam results to see if I could do the degree course at the Royal Academy of Music. So I needed certain grades to do the degree course. You didn't need those exams if you were going to do the performers course, but I really wanted to do the degree so that I had something to fall back on if need be. So I just done my exams and I had to wait a few months in order to get the results of those, which is quite normal up there. And but meanwhile I had the opportunity to audition for the Royal Academy and the Royal College of Music, both in London, and they're both equally good places to go to. But I had no intention of ever being accepted at that time. I just thought I'd do it for the experience and because I had no idea what level I was on a national scale and it was important for me to get some kind of inkling of that. And so I auditioned I think the first one was the Royal Academy and I felt the audition went as smoothly as it could. I did the best I could. There's nothing more I could really have given and, however, when the letter came from them, they decided not to accept me because of my hearing impairment, and so I was quite confused by that and a little frustrated and thinking well, that's odd. You know, what about the audition itself? Did it go okay or not? So basically it was on the level to get in or not, and that was the key question. So their concern was that a professional orchestra would not at that time have hired a musician with a hearing impairment. And I said, well, I don't want to be in an orchestra, so you're creating a scenario that does not exist. And I want to be a solo percussionist. And of course this was almost like a double whammy for them, because solo percussion on a full time basis had not existed before. So you know, the panel could not envisage a percussion recital at, you know, the premier halls in London or something, and. But I said, well, that was my problem, I had to work out a way to do that. And so I did push about the audition and to get an answer whether it was good enough or not. And they said, well, actually it was good enough. And I said, well, you have to create a place.

Speaker 2:Then, and it was one man on the panel who kind of said to the rest of the panelists well, hold on a second, we can't start judging people just because they're deaf, they're blind, they might have one leg, one arm or whatever it might be. You know, if they are off the standard to get in, we must offer a place for them to get in, if there are enough places, of course, you know. And and there were places for the percussion. So he said you know, we're on kind of dodgy waters here and and I think we need to call this person back for a second edition and if that second edition is still acceptable, we have got to let her in. We've got to offer a place.

Speaker 2:So I had to trope back from Scotland to London again and do a completely unprepared edition.

Speaker 2:So none of this had any percussion playing at all, it was all done at the piano and it was things like figure base transposition, looking at scores, thinking who might have composed that and why, choral reading, orchestral score reading, transposition, I think I've said, and all sorts of things, and and so once that had been done and those were things that we used to do, you know, at school, so it wasn't completely horrendous, and and so after the edition, immediately they said you can start in September.

Speaker 2:Of course I was still very young, but I felt completely ready to leave school, I felt completely ready to start the full time studies as a musician and that was it. But the outcome was that it changed the landscape for future people who were auditioning, who happened to have various challenges, physical or otherwise and and that all auditions were based on ability and what the panel felt that they could work with and improve. You know where they could sense the sense, kind of that feeling of improvement within the individual and and that was that. So once, once I got in, it was a case of getting your head down, concentrating, making use of the time and working very hard indeed.

Speaker 1:It's an amazing story. What, what I feel like asking you is what comes to mind is where did that clarity of vision come? When did that cut? You're so clear about what you wanted. It doesn't sound like you wanted to necessarily prove anything because you didn't see yourself that way, but you did. You did want a fair opportunity. That's right, I mean. So talk to me about. Where did that come from? That sort of I guess it's agency, it's not really tenacity, what I don't know, what would you call it?

Speaker 2:I don't know what it is, but I think we all have it and I think that it's. It's a case of the kind of surrounding landscape that you have. You know, I went to a normal secondary school, you know, in in North of Aberdeen in Scotland, and and it was a school whereby they believe that every child has a story to tell and so they're not looking for every child to to score A's in every exam. That's not what it's. What it's about, it is literally making sure that that school provides for children and to give them opportunities. So the school wants to have a really great plumber, a great chef, a great electrician, a great speaker, a great sportsperson, a great musician, a great artist, a great whatever it is, a great housewife, a great husband, a great wife, a great housekeeper, a great cleaner, a great shopkeeper. You know all of these things were important. So they knew that every child is good at something, is passionate about something, is curious about something. So they made sure that all departments of the school were open to all kids, no matter what their situation. So for me, as a young kid, you know, trying to find out how to negotiate hearing aids, how to negotiate music and the aids, and thinking that what we hear is through the ear. They gave me that opportunity, through the skill of a peripatetic teacher for percussion, along with a peripatetic teacher for the deaf, to really work together and to make sure that this particular youngster, you know, was supported in every way possible.

Speaker 2:And I remember the visiting teacher for the deaf, you know, who came in. She was not musical at all. She realized that I was quite passionate about music and she happened to see something on television at the time about an organization called the Beethoven Fund for Deaf Children. Now she thought, oh gosh, you know, I think I'm going to write to this fund and see if I can get advice as to how to support this young pupil that I've got, because I've got no idea whether she's going to make it in the music industry. Of course she was coming at this from the deaf standpoint because that was her expertise, and so she just took the chance to write a letter, a typed letter, so this was before email and so on.

Speaker 2:That started with. This is a cry from the heart. But I've got a young pupil here who's passionate about music and wants to do music as a profession, and it goes on and on, and she then gets a reply from the organization and that kind of you know sort of created another bit of the puzzle or another brick in the building, if the journey really, or the road, or however you want to call it. And so again, you know, a journey doesn't happen in isolation, it's keeping your antennae open. You know just asking, well, what if? So that teacher just said to herself well, I've seen this organization, what if I write to them? Who knows? It's as simple as that. And that just keeps going for the rest of your journey. You know, my particular, you know career has just been built on that. You know it's peeling the next layer, opening the next door. You know, peeping around the next corner just seeing what might be there. Yeah, why not right? Why not? Absolutely exactly that. And that's what kids do so well, naturally, and that's what we want to keep going.

Speaker 1:It's true and as I said that out loud and thought about in the context of children, you know, when we reprimand them, they're always global. Why not, absolutely? Yeah we always have a quick answer and a reason, you know, based on talk about, you know, perpetuating limiting beliefs. My God, exactly so funny. Do you have children yourself? No, I don't. You don't, okay, and it was all your instruments.

Speaker 2:I'm sure your children to a big extent. They need a lot of looking after. They can be temperamental and they can go their own way.

Speaker 1:Yeah, no doubt, no doubt. I'm curious have you ever, or have you, stayed in communication with that, that woman that wrote that letter?

Speaker 2:No, not at all, actually. No, I and I don't know where she is now and or indeed if she is still around, but certainly the founder of the Beethoven Fund, anne Rachlin, who very sadly passed away a couple of weeks ago. We kept in touch really since that very, very beginning stage, so as soon as I met them after that letter was written, we kept in touch for all the years thereafter.

Speaker 1:Oh, lovely, Isn't that? Isn't that wonderful, right? Those, those threads.

Speaker 2:Absolutely yeah, and it's. It's another example I think of you know, it's certainly an Anne's case digesting her legacy and and you know what she had done and what she was still so determined to do. And so, certainly through my foundation, I want to keep her legacy alive. I want to really draw upon that. I draw upon a lot of the things that she embarked on and she said and the interactions that we had. There's a lot of inspiration for me and and and I certainly use that as a springboard a lot- yeah, it's interesting.

Speaker 1:I often ask my guests, you know, if you could go back and, you know, talk to your younger self and tell them something that you know, based on what you know now, maybe what, what they would have liked to have heard when, when, when I think about you and asking you that question, I think Maybe it's the other way around. My instinct tells me that you're very in the moment. Then, I mean, my thing is called right being in the moment. I get the sense that you are so in each moment, that it's not attached particularly to any sort of outcome other than what happens in the moment, and that you're, yeah, talk to me, she's not here.

Speaker 2:Yeah, I think you're right there. Actually, I think it's and I don't know why that is it might be because, you know, as a musician, when you perform, live, you know that is the most important moment. You know that you're dealing with. And I think when you spread that out, you know the person in front of you is the most important person. So at this point in time you're the most important person in my life, because that is what you know, whom I'm talking with, communicating, with addressing, you name it. And so I mean, can you imagine our conversation? If I was, you know, had my mobile phone sort of here right next to me and I'm kind of looking at my mobile phone as I'm chatting to you and you know my head is sort of moving here, there and everywhere. I mean that would be highly distracting and you would know that the focus is not really on this conversation. So, and I think with music, you're, you know, always dealing with that moment, even in a practice session, you know.

Speaker 2:I think that's why it's sometimes detrimental to encourage young musicians when they're starting out. You know you must practice for hours and hours. Well, actually, you know, let's think about what you can do in 10 minutes. What can you do in 15 minutes, what can you do in 20 minutes? And then, gradually, people just feel the time scale that's right for them, the kind of duration that's right for them.

Speaker 2:So, at the moment, because my life is just, you know, doing all sorts of bits and pieces, a lot of the things I do are non-musical. So there can be admin based, or there can be, you know, you can be in meetings, you can be doing all sorts of things, and it's, you know, quite a while before you can get to an instrument. So therefore, 10 minutes matters, you know, and what kind of headspace are you in that time period and how can you make the most of that? Or it could be that I'm, you know, at a venue but I'm not able to get onto the stage because of unions or something you know, or there's nobody there to switch the lights on, or whatever it is.

Speaker 2:So what is it that you can do in your dressing room? Then, you know, and it's all of this sort of situation, especially as a percussion player, where you don't have access to the instruments as and when you want, certainly in the line of playing that I'm involved with. So you find all sorts of ways to connect with trying to improve things without actually having the most obvious tools. So how can I practice without having the instruments basically? Or how can I think of things without having X, y or Z? So that's often the situation.

Speaker 1:Yeah, that's an expensive, really truly an expensive, way of growing your art, isn't it? Because you know it would be easy to fall into the mindset of, you know, feeling that those lower frequencies of what do you mean? I can't get on the stage right now, and you know what I? You know, oh, I can't practice in my hotel room, so you know. And then a lot of energy and fear starts coming in, Whereas as you're saying is no, I just get curious, you know. You take it as it is. This is true.

Speaker 2:Yes, absolutely, and you know every situation is different and yes, and it just kind of helps you deal with the moment in time and some things are out of your control, and that's that, you know, and other things you can maybe influence a wee bit more, and it is again that's kind of a form of listening. It really is. So everything is a give and take.

Speaker 1:Yep, 100%, 100%. I wanted to ask you. I want to ask you a lot of things. What should I ask you? What's the hardest thing you've ever done?

Speaker 2:Oh, I don't know, that's an interesting question. I'm not sure if I've really thought about that. I don't know the hardest thing. It depends whether you can sometimes confuse the hardest thing by the outcome and think then that oh, that was really hard because maybe the outcome didn't kind of you know, you can't really, you know you can't really, you know you can't really think really hard because maybe the outcome didn't kind of, you know, come to the conclusion that perhaps you wanted it to.

Speaker 2:I mean, I've played some pretty hard pieces of music that have been a real kind of struggle practicing, and again, that can be a challenge, that you find ways to get around and so that happens, but that you know that can happen quite a lot actually. So I'm quite used to that and I see it more as a challenge than something that is hard. That's a really interesting question and I'm not sure if I have an actual answer. I mean, there can be things that have cropped up whereby I thought, oh, I could never do that and actually when you're pushed to it, you just do do it, and it could be a simple thing, like I remember, you know, when I started out as a young player and I was just sort of playing the pieces on stage and somebody said, well, you need to kind of speak to the audience, you know, and it sounds so normal now.

Speaker 2:But, and I said, oh gosh, no, I don't know what to say. You know, I just sort of stand there and then nothing would come out of my, my mouth. And they said, no, no, just give it a go. And but I can't say, I kind of put that into the category of being hard. It was just, oh, that's out of my comfort zone, and it kind of very flippantly say, oh, no, I don't think I can do that. And it's easy for anybody to say that. You know, we often say that, oh, I can't swim, or oh, I could never dance, or oh, I could never play the bassoon or something.

Speaker 2:Well, of course you could you know, if you have the physique to and the kind of support. You know I'm five foot two and there are. You know I'm never going to be a six foot model, you know it's not going to happen. So that's that. So you only have what you have in order to work with and and that's that. So I might need to consider your question a little bit longer.

Speaker 1:I love that I'm saying I love that it's always so interesting to, when people are truly pondering something, to know where they go to look for the answer. Where was your first? Where did you first go when you received the question to look for the answer?

Speaker 2:And well, I don't know, I think that's. I mean, there's obviously the obvious place, such as a hard piece of music. You know that you had to find a way to enjoy. That was the kind of immediate place and the most obvious place.

Speaker 2:But you know, I've been in a situation musically whereby I simply thought I was not the right person for this particular repertoire and I nearly went back to the, the group and the composer to say you know what, I'm not quite sure if I'm the right person here, but actually I just kind of spent another day or two reflecting on it and persevering and bit by bit, by bit, slowly but surely, you know, I just kept myself going with it and and although it took ages to engage emotionally with the music, now, after you know, a few years and a few recordings and a few performances it's, I find it very satisfyingly challenging. You know, and I know that I'm not going to get the emotional input immediately, as I do with a lot of other repertoire, and I know it's going to be a hard slog and I know there are certain hoops that have to be gone through, but that's my choice.

Speaker 1:Yeah, no, that's really interesting and you know, if we were talking longer, I dig in with. I wonder if the difficulty was not actually in the piece, but with coming to terms with how you felt about the piece, right? Not, I don't think there's ever a question that there's something that you can't do, probably musically. I think it's pretty fair to say that if you put your mind to it. But the right, yeah, yeah, I think.

Speaker 2:I think so. I mean, I think I think it's also the feeling of what feels right at this point in time and I'm not saying that everything should feel easy and because it's really healthy to be out of your comfort zone and it's just kind of registering right. Are you willing to be in that position? And in this particular case, I felt that I was in a position where I was felt give yourself another chance with this. And so the rewards have kind of come. And again, you know, this just goes back to listening. It really does. It really really does. And I can't emphasize that enough and we're all different there, you know.

Speaker 1:Yeah, and it's so true because you have options of what to listen to as well, right, just as we talked about with the children, they're open to listening to everything. We want them to focus and listen to us, or, you know, listen to the message and what yours. And when we encounter that kind of experience that you did, you know there was you. It sounds like you were confronted with one way of listening and that kind of stopped you for a moment, going, oh, you know, maybe I can't do this. But then, when you opened up to it and got more curious, you realize no, no, there's other ways of hearing this, hearing my voice in my head, right?

Speaker 2:Yeah, I think that it's finding the entry points that are that are perhaps not the obvious entry points, and I think that's that's always fascinated me, because that that's what happened when I was at school with my peripatetic percussion teacher. You know there was, you know you just didn't enter things in the most obvious way. So the very fact that we were playing, you know, a Bach violin, per quitter on the snare drum per quitter on the snare drum, for example, you know that that's not your usual entry point in learning how to play a snare drum and or being asked to to, you know present the feel of a tractor as opposed to the sound of a tractor, that's not an entry point and it's great because then you're on the road then to something that is is some, just full of curiosity, which is is what?

Speaker 1:Yeah, that's brilliant. So what? Oh well, I suppose I should ask you what's the easiest thing you've ever done.

Speaker 2:Oh, I don't know these things at all. Oh, I've got no idea. I think probably the well, I'm not sure if it's the easiest, I've got no idea. But I think what I found pretty easy was making the decision to be a solo percussionist. I mean, there was just no, no debate about that. Once the decision to be a musician had been made, then the decision to be a solo percussionist was was absolutely as easy as pie. There was just no, no kind of other consideration there. So I think that was pretty easy. Easy to make, yeah.

Speaker 1:No, that makes sense. If there were three words that you could use to describe yourself, three adjectives, what would they be?

Speaker 2:Oh Crumbs, you're really asking some questions here.

Speaker 1:I know you're a deep thinker, I know you can handle them.

Speaker 2:Oh well, I don't know. But I don't really think about myself that much, but I've got no idea. I think, probably, I think I'm determined, I'm curious for sure and I don't know. I'm looking for help here. I'm kind Kind, yes, oh, I'm just looking at Emma here. I don't know.

Speaker 1:You're kind.

Speaker 2:Yes, they said kind.

Speaker 1:Well, what's really interesting is if Thank you, crumbs, this is fun. Well, it's interesting because I bet, if I asked you first what are three adjectives that others might describe you as, would that be easier for you to know how you're perceived. Maybe not, I'm just curious.

Speaker 2:I think I'd dive under the table. That's amazing, that's super cool.

Speaker 1:Yeah yeah, I'm just curious. I totally vibe with you on the curiosity thing. I'm not attached to, it's just so interesting. You never know what might turn up. What is your definition of living in the moment? Do you actually sort of have one or do you just do it? I know you're good at it. I can tell you they're very good at it.

Speaker 2:Well, unless you have a definition other than I know that this word is coming up time and time and time again in our conversation. But listen, I think, is such an important word because I think it is that connector even in the heat of a debate or in the heat of an argument, or the heat of frustration, or the heat of celebration or happiness or any kind of emotion possible, listening to that here and now and that emotion happening in the here and now is what we remember. That's, in a way, what we feel as being memories. It's not often the thing that was given to us, that object or something. It's kind of the feeling of receiving that object or what did that make us feel like, or what did it feel like to give that to somebody, or whatever it is.

Speaker 2:I'm kind of looking across at Emma, but Emma gave me last Christmas a very lovely little candle Now a candle. There's candles all over the world and people give candles to people on all different kinds of occasions, so that was very nice. Thank you very much. It's a really nice candle, but it's a feeling of what that candle does. So when I pop the candle on in the studio at home as we're maybe doing a recording or something like that, and this kind of smell wafts in the room. It's a kind of feeling that is ignited with the candle. So although it's an object and you say thank you, it's then the kind of how this spreads.

Speaker 2:So that's a kind of simple definition of, I think, how we can ignite our own memories in what we're given or what we give or something. So it kind of gets away from being entirely materialistic and feeling oh Krums, we have to have something before we feel happy. We can really be happy with ourselves with not a lot, and you can find something as you go out for a walk and it gives you a feeling. So it's listening to that feeling, it's acknowledging that feeling. I guess it's sort of stripping out a lot of what we feel we need to have. We don't need to have so much 100%.

Speaker 1:No, I hear you, and it's where gratitude lives, right? I mean you can't really be in gratitude or listening which go together unless you're in the moment, can you? I mean you can't really listen unless you're focused on the moment.

Speaker 2:Yeah, true, and I think with listening I mean it does need reflection, without a doubt. So you can, and I do it myself, I know I do it myself and I kind of you know where I sometimes jump in or I make assumptions or I might kind of almost finish some of these sentences or I might just have a, you know, a kind of snap feeling or whatever, and then I just think to myself you know, there you go, just step back a little bit here and give time and space A chance to be felt.

Speaker 1:Really, yeah, something that I write about a lot and that I really identify with is what I call the places where there are spaces. And you know, as a fellow artist, I'm a tap dancer. I'm a dancer, I do all sorts of things, but I identify quite strongly as a tap dancer and you know I've always thought about how important those places where there are spaces are. I feel like that's what you're talking about. You know that you cannot have unless you have yin and yang. You know you need what happens in between. That's where life is. I used to always say when I was teaching the dance you know it's, you can learn all the technique and that's important, but the dancing happens in between, right, it's in the essence.

Speaker 2:Absolutely it is. And, yes, we often talk about the notes. You know, in between the space, in between the, and that's what resonance really is. You know, that's kind of where the body language of sound comes in. You know, it's the equivalent of speaking like a computer, with no inflection, no variation in dynamics or accents and no full stops or commas and things like that, and and likewise, you know, with, with music, it needs that resonance, it needs the space, it needs the acknowledgement of the acoustics in the room, and it goes on and on and on. And that's really what the, the kind of sort of well, yeah, the body language of the sound is. And that's then where the story comes into play, because we all have different body languages. You know, we will have our own quirky ways of doing things and moving, and the pace of our walking, or the, how we smile, or how we move our heads, and so on and so forth. And that's exactly the same with, with sound and how we negotiate sound.

Speaker 1:Yeah, the coolest thing about sound is that, well, you can't really see it, or at least not at first sight. You can't see it right.

Speaker 2:Absolutely, and I think that's the uniqueness you know, offside, as you give a concert and people can't walk away with it. Having said that, of course, now with everyone having their phones and and being able to to, you know very often video things and have snippets of this, and that I think it is really changing the way we listen and the way we engage with things and the depth of that, because it's then no longer a physical thing and it's a memory that has been kind of frozen and being frozen in time, but then it makes the mind a tad lazy, you know, because you can always just switch your phone on or whatever device and remember, and of course, there are certain advantages to that in certain situations. But I think the depth of memory and reflecting and having your own space to do that really keeps that story alive. It really, you know, builds on the feeling and it will change that feeling as you go through your life and you then have a much better perspective as regards to where it sits in history, and I think that's so incredibly, so incredibly important. I mean, for example, here this is where we house the Evelyn Glennie collection, which is part of the foundation, the Evelyn Glennie Foundation, and you know, you see the kind of trajectory of correspondence from handwritten letters to typewriter type letters, to then faxes to emails, and you can see how vocabulary has changed, how you've gone from handwriting to a typewriter to then email.

Speaker 2:You can see how sentences suddenly become much more clipped and short when email comes into play. You know how there's less kind of respect in saying dear, so and so, best wishes or kindness, regards, as you might do at the end of a letter or whatever. You know it's none of that really to such an extent exists in the way that we communicate now and again those pros and cons to everything. But when I look back at the letters I can feel the occasion, I feel the person, I can feel that conversation. You know it's a completely different feeling than when I read an email. Yep, I just see all emails as kind of this long list of emails in your inbox without any personality. When I see all these addresses, yeah.

Speaker 2:And it's a completely different kind of sensation and I think it'll be very interesting to see how society is in 100 years time, 200 years time, 500 years time, to see how we'll all be communicating.

Speaker 1:Yeah, that's really, really fascinating and it's a really interesting way of looking at it, and it's so cool that you have that, that you can actually sort of see how it's changed. It's amazing, isn't it? Because resonance, as we were saying, is in the receiving as well. So if we're so quick, I mean, it's like jamming with somebody who jumps on your toes right or doesn't hear what you said in order to respond, and we're missing all that in our rush of our lives just to do things quickly, so there's never any moment to embody anything.

Speaker 2:Absolutely yes, indeed, and again sort of referring to the foundation and the collection and its mission to teach the world to listen is so incredibly important because that taps into all different landscapes, from medicine to sport, to music, entertainment to education, to religion, to business, you name it you know, the kind of spine of what we do is listening, and most of the issues that we have and the challenges that we have are to do with listening, you know, whether domestically or work wise, and so it is quite fascinating.

Speaker 2:I mean, last night we had two groups of scouts in to look at the collection and see some of the instruments and so on. And you know, these are young sort of teenagers, you know you're looking at 13, 14 years old or so, and it's just fascinating for them to be in front of a great big tam-tam, you know, holding that great, massive, woolly mallet, you know, and there they are striking the tam-tam and just feeling that mallet on the tam-tam and waiting however long it takes to for that sound to disappear and for them to just be standing there allowing the sound to seep through their bodies. And you know one of the instruments, you know I, we're just sort of playing and immediately one of them said my God, I can feel that through the floor. Now, you know, you wouldn't normally get a 14 year old or 13 year old, you know, saying that they might say, oh, that's an interesting sound, or oh, I haven't heard that sound before. But the very first thing they said wow.

Speaker 2:I feel that through the floor is is interesting, you know, and that's what we're asking them to, to just be aware of that. They have the opportunity to open their bodies up like a huge ear and with that might give them some patience when they have a conversation or before they reply to an email, just thinking, aha, you know what, I'm going to create some resonance here before I just jump in and reply to that. I'm just going to reflect on that. Or, oh, you know what, I'm going to give myself five minutes longer just to digest this math problem or whatever it is, rather than getting into a state of frustration or feeling they've got to immediately go on YouTube, to, to, to work out a short route to it, or something.

Speaker 1:Yeah, oh yeah, 100%. I mean the work I do as a coach is people say to me what do you do? Go I, I listen and I ask questions. And they go. What do you mean? You listen and you ask questions, that I listen and ask questions. Well, how does that work? And I say to them I, I listen not to what they're telling me, but to what they're telling themselves. And that's where the questions come from. And it's amazing because, because people are not listened to, nor do they listen to themselves, I mean, they listen to themselves in one way, right, the dominant default.

Speaker 2:Yeah, I think it's a really. It's kind of a necessary and a very precious activity that we can all involve ourselves in is listening to our own self-talk, our own conversations, a bit like putting your own life mask on first on an airplane or something, before you help your, your fellow passenger, and at first you know. When that sort of was shown, I thought, well, well, that's a bit selfish. You know you need to make sure that your next door neighbor has got their mask on, and then you get yours on. And then I thought to myself well, actually it does make sense that you put your own ones first, because if you're not breathing, you're no use to your fellow passengers. So there you go.

Speaker 1:Yeah, no, absolutely. I could speak to you all day. I would love to speak to you all day, but I know I can't, I know you're busy. So let me ask you this oh well, how do you recharge? Is that something that you feel that you need, or you know? How do you, how do you dynamically, sort of you know, get through your day, for that matter? How do you recharge? How do you replenish?

Speaker 2:yourself. Yes, I mean, I'm not the best at taking holidays by any means, but you know, I think that I do like my own time, I will say, and that is possible to do, because I do live on my own and I enjoy living on my own, but at the same time, I like to connect with people, which is why it works really well with the setup that we have. So, you know, I'm not a recluse or anything, but I do enjoy kind of having that space. And, of course, a lot of the work I do, especially when you're practicing and traveling around, it's often done by yourself, on your own, and so I'm used to that scenario. But I think it is important to just have your own time, your own space, and that is often as good as a holiday, you know.

Speaker 2:It can be just a simple, simple things like going out for a walk, you know, or going out for a cycle, or, you know, I enjoy going to antique stores and fairs and that type of thing, and that's a release. That's just, you know, something that I like to do. I think for me what would be more stressful is packing a suitcase, getting on a plane, going to a beach or something, you know I don't want to live out of a suitcase when that is sometimes what you have to do in your work, so that to me it doesn't make sense. But that's just me. For other people it could be absolutely the thing that they enjoy and want to do. So, I think, each one to their own really.

Speaker 1:Yeah, no, absolutely, I hear you. I mean in those micro moments right where you can just sort of go off and take a breath and take a walk, I mean that's enough, right? Sometimes I mean just I mean yeah, yeah, yeah yeah, Is there. If there was one highlight and one low light in your career so far, what, what, what would those be?

Speaker 2:I think a highlight, an overall highlight, would be the fact that solo percussion does not have to be talked about, whereby it's an unusual thing. It is a normal thing now and it's a thing whereby young players are embarking on without being seen as unusual or anything like that. So there's the repertoire there to start the career of a solo percussion player, and that was an important part of my aim was to make sure that a player did not have to wait X amount of years before enough repertoire was was there in order to sustain a career and it's important to use that word to sustain a career and so there's definitely repertoire out there for that to happen. Of course, we all had to participate in the commissioning process still, but nevertheless, it's absolutely possible for a young player, if that is their mission and passion, to start immediately a career as a solo percussion player. So I think that's the overall high. Actually, there have been many performance situations that have been very exciting. Of course, there are. Probably the most recent one, I would say, and even that is back in 2012, was the London opening ceremony of the Olympics. I mean that was an incredible high, more for the country, and again, it's sort of zooming out of the situation. That was an amazing, an amazing event and it changed a lot of people's lives actually. So that was definitely a high point. But, as I say, the overall high is making sure that and showing that the sustainability of a solo percussion career has been possible.

Speaker 2:The low points, I mean they're kind of more for nicotine and fiddly and whatever. There's never been such a low point where you felt I'm going to pack it in. No, there's never been that kind of low. There's been, frustratingly. There's been frustrating moments that have got you down a bit or haven't quite gone your way, but they've never been enough to kind of tip the cart where you think you know what. I've just kind of had it now. So I think I'm kind of grateful for that. But, as we've kind of talked about all along, you just take each day as it comes. Obviously you have your aims and visions and all of that, but ultimately it's a here and now that you're having to address and deal with and acknowledge. So that's the situation.

Speaker 1:Yeah, no, that makes sense. You've built already such a legacy and I know that you have a long way to go. I read somewhere about yes, what am I going to do for the next 20 years or 30 years, and I'm curious to know what does that look like for you? What do you want your 30 years, 20 years from now?

Speaker 2:Well, I think that everything that's happening now can continue to develop, but it needs to develop more. I think, obviously, as a player, which is very physical, you know that that's not going to go on forever. There will be a time when you think you know what, I'm ready to hang the sticks up, and again, that's a natural progression and that's again a form of listening, and an important form of listening, and that will have to be addressed at some point. But certainly the work of the foundation and the ongoing development of the collection is hugely important to me and they both must sustain even when I'm not around, so it can't just be dependent on me. And so that's really what we're working towards and making sure that the collection is always added to, that it's always a living collection, that it's curated well, that it continues to enlarge in its instrument collection, its musical scores, its books about percussion, its books about deafness, it's all sorts of things, and so we very you know, are always excited to receive donations or any instruments and things like that and to make sure that we have the provenance and make sure that they are exposed to the public. So our next step there is to get the funding for a database so that people can access the collection from all over the world.

Speaker 2:And what's important about it is that it tells a story. So you know, when it comes to the instruments, we're not interested in saying, oh, here's a marimba and it comes from X, y or Z. We want to know what is the story of that marimba, what is that symbol or that snare drum or that conga, and how it relates to the whole journey of what the collection acknowledges really. So it's also open for research. So we encourage students to come here and use it for research. So an example is that one lady did her PhD here using the collection and she's now gone on to write a book which will be published next year, whereby the collection was a huge resource for her with the book. So we're keen for that because it touches on social aspects, it touches on gender, it touches on instrument manufacturing, it touches on repertoire, it touches on geography. It touches on all sorts of things Obviously my relationship with charities and organizations. It touches with the development of sound and deafness. It touches on an awful lot than what you think is the obvious thing. Ie percussion.

Speaker 1:Absolutely, and I will absolutely put all sorts of links in the show notes for anyone that wants to get involved. There's so many different ways to get involved. That's wonderful. Thank you, it's really truly amazing. That's a quick question, a quick question. This is not a quick question. Well, maybe it is for you. What's something that you might do if music did not exist in the world, for God forbid, whatever reason? What would you do?

Speaker 2:have some peace and quiet.

Speaker 1:No answer.

Speaker 2:Oh, I don't know, I would. I do like animals and and, of course, having been brought up with animals on the farm, I think I'm always sort of intrigued what it might be like to work with animals in some way. I don't have the brain to be a vector or anything like that, I just mean, and you're training animals or, you know, supporting animals for deaf people or blind people, animals, you know, being trained to go in prisons. You know dogs and cats and things like that, or looking after animals in some sort of way, but I like the feeling of training them so that they can kind of be an extension to to our ways of living, you know. But yeah, probably something to do with animals, I suspect.

Speaker 1:That's cool. You make jewelry too, right? I read somewhere yeah, used to.

Speaker 2:Yeah, it's something that we've kind of shelved now, really partly because of time. But yes, I love jewelry and and always have done. My mother's side was Arcadian and and they had a particular style of jewelry and do have a particular style of jewelry and and Orkney and the Orkney Islands, which are just right at the north of the mainland of Scotland and and I remember being so intrigued by that as a little girl when we used to visit relatives there and and it kind of started from that and then collecting jewelry. And then, as I began to travel around, you would, you know, pick up bits of ethnic jewelry from you know, like Maori jewelry in New Zealand or Aboriginal jewelry or American Indian jewelry and all sorts of things you know, really beautiful, lovely pieces, and and it was just like percussion. You know you're just picking up instruments from everywhere and it was a you know same with with jewelry really.

Speaker 1:Yeah, no, that's that makes sense. That's really interesting. We play this little game and I say what makes you okay, what makes you hungry? Curiosity, what makes you?

Speaker 2:sad Laziness. What inspires you Seeing a team work well?

Speaker 1:What frustrates you?

Speaker 2:Laziness again.

Speaker 1:Still laziness. What makes you laugh?

Speaker 2:Making fun of myself.

Speaker 1:And what makes you angry?

Speaker 2:Laziness.

Speaker 1:And finally, what makes you grateful. Oh heavens, just being alive I think, fair enough, that kind of encompasses everything, doesn't it? Yeah, yeah, so yeah, absolutely Brilliant. What are the? What are the top three things that have happened so far today?

Speaker 2:Oh heavens. The top three things have been having a really robust, productive meeting to do with foundation matters so that was good where people could really you know, just air things, and that was great. Another lovely thing that happened was having an online session with a law and accountancy firm that had offices up and down the UK and seeing how seriously they think about inclusiveness and listening within their company. So that was really, really inspiring for me. I think that was definitely a highlight for today. And another top thing is that we've had no power cups and no disasters happening in the building so far, so it's still got a roof over our heads, so that's a good thing as well, and what's something that you're looking forward to both today and then in the future.

Speaker 2:Well, I think today is just now getting home and just having a moment to digest what's happened today. So that's a nice thing and you know, that can be a kind of healthy moment and I think in the future it's really getting to the end of the year and wrapping things up for the year and getting the priorities sorted for the new year and kind of that feeling of starting a fresh new year again.

Speaker 1:Yeah, yeah, it is that time of year, isn't it December already? It's crazy, evelyn, listen. I so appreciate spending this time with you today. Really, it's been an absolute pleasure.

Speaker 2:Thank you very much. It's been fun. Thank you, yeah.

Speaker 1:Oh, it's my pleasure I've been speaking today with Evelyn Glennie. I'm Lisa Hopkins. Thanks so much for listening. Stay safe and healthy, everyone, and remember to live in the moment. In music, stop time is that beautiful moment where the band is suspended in rhythmic unison, supporting the soloists to express their individuality In the moment. I encourage you to take that time and create your own rhythm. Until next time, I'm Lisa Hopkins. Thanks for listening.